INTERSCALENE

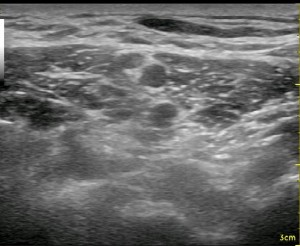

Converting from nerve stimulation to ultrasound for an interscalene nerve block classically involves going to a more posterior approach. This is also the case when changing from the traditional single injection to a continuous nerve block. For reasonable catheter securement issues as well as optimizing visualization with ultrasound, it becomes necessary to enter the skin several centimeters away, sometimes as far away as the trapezius muscle for catheter placement. The image to the left demonstrates a reasonable approach to the brachial plexus with the needle sitting just behind the 5th and 6th anterior cervical nerve roots (with a reverberation effect). The needle has passed through the middle scalene muscle (seen just above the needle). The anterior scalene muscle is seen to the left of the round nerve roots. A slip of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is seen as a relatively thin dark patch in the upper left-hand corner. If you plan to push the needle through the middle scalene muscle, I would advise a slow and steady pace as the dorsal scapular nerve may traverse through the muscle belly as well, and it can become entrapped by your needle to cause a (likely short-lived) neuropathy. The slower pace allows the nerve a better opportunity to be pushed out of the way and for your nerve stimulator to detect it as you approach. It can be seen as a short, white line that is thin and crooked. When I recognize it, I choose a needle trajectory that will avoid it.

Note that the brachial plexus does not appear straight up and down; the plexus actually leans backward against the middle scalene muscle exposing its anterior surface to the more superficial approach of a traditional single injection nerve stimulation technique (where you place the needle between your fingers which are opposing the anterior and middle scalene muscles). Just as in the spinal cord, the nerve fibers on the anterior surface of the roots at this level are motor fibers, so some twitch will be anticipated almost all the time. As well, the posterior fibers are sensory at this level. This orderly, separated orientation of nerve fibers is quickly lost as you move distally beyond the roots, but when approaching from the posterior position, it is far more likely to elicit a paresthesia and no motor twitch at all. The patient should be told to indicate to you when a sensation going toward the deltiod and biceps muscles occurs as you approach the C5 and C6 nerve roots. This also makes it more important to keep from significantly sedating a patient, expecting a twitch to indicate proper needle placement. It is typical that almost immediately after performing the nerve block from this approach, the patient is unable to flex their deltoids (I ask them to reach their hand up toward the ceiling before and after the block). Because of this nerve fiber arrangement, however, it is not uncommon for a patient to be able to move his or her hand though they have no pain in the shoulder and upper arm. This is an important point when evaluating post-operative pain in the PACU. Just because someone can move their hand does not mean the block was not well-placed. Start your evaluation by determining if the patient can recognize numbness or tingling in their index and middle finger only.

When approaching from the previously stated posterior position, it is far more likely to

[nonmember]

REGISTER for FREE to become a SUBSCRIBER or LOGIN HERE to see the full article!

[wlm_ismember]

elicit a paresthesia and no motor twitch at all. The patient should be told to indicate to you when a sensation going toward the deltoid and biceps muscles occurs as you approach the C5 and C6 nerve roots. This also makes it more important to keep from significantly sedating a patient, expecting a twitch to indicate proper needle placement. Because of this nerve fiber arrangement, it is not uncommon for a patient to be able to move his or her hand and have no pain or other sensation. This is an important point when evaluating post-operative pain in the PACU. Just because someone can move their hand does not mean the block was not well-placed.

There is controversy as to exactly where the local should be deposited in this nerve block. Some advocate for a ‘less invasive’ position posterior to the nerve roots, creating a crescent shape behind the nerves and anterior to the middle scalene muscle. Others recommend piercing the thin plexus sheath, which is noted in the above picture surrounding the superior trunk, and depositing local within and around the sheath. Some even place the catheter intentionally anterior to the plexus in order to allow ‘track back’ (discussed in the Femoral Nerve Block section) to work for them. Both techniques produce reliable nerve blocks, and it would take an enormous study to say that one is associated with more nerve injury than the other since complication rates are so minuscule. As in so many other aspects of learning nerve block techniques and implementing aspects of a nerve block program, it seems prudent to start with the least invasive technique until one achieves a better ‘feel’ for this and a myriad of other variables before considering this more assertive approach.

Another popular technique among experts is to ‘flip’ the catheter behind the plexus. This technique is where the catheter is seen exiting the needle and pushing against tissues and extending enough that it flips over. The idea is related to the typical multi-orifice orientation of the catheter and creating some extra slack in the line to account for shoulder and neck movement by the patient. The multi-orifice catheters have holes that may be within the body of the middle scalene muscle if the end of the catheter was in contact with the brachial plexus, so extending the catheter end further into this gutter helps to deliver local anesthetic to the plexus.

Note the proximity of the PHRENIC NERVE to the brachial plexus in the image above. It lies on the anterior surface of the anterior scalene muscle which is attached to the first rib. Utilizing catheters and the posterior approach gives you the opportunity to provide superior analgesia to many individuals with severe COPD who are having shoulder surgery. COPD is a relative contraindication to placing an interscalene nerve block due to the concern of respiratory insufficiency with a traditional dose of local anesthetic. One is also confounded by the notion of considering a relatively small amount of local anesthetic in this circumstance in order to avoid significant spread to the phrenic nerve. Even if this is avoided, the bolus will have a very short duration. This leaves one in an all-or-none position because even a small amount of long-acting local anesthetic can cause respiratory issues. My strategy has been to bolus only about 5 mls of dilute short-acting local anesthetic (Lidocaine 1%) through the needle to confirm appropriate spread, then gradually ‘titrate up’ the dose very slowly using minimal pressures through the catheter after it is secured in place. I have found that I can often inject up to 20 mls of local and provide excellent post-operative analgesia without respiratory compromise even to oxygen-requiring patients. Though sometimes I am not able to give a higher dose and ‘even better’ analgesia, I am able to provide some analgesia and avoid greater amounts of opioids which are also problematic for these same patients. Again, I would advise caution when considering such a strategy to anyone who has not placed a significant number of continuous interscalene nerve blocks and has not had the opportunity to develop their skills in patient evaluation in similar circumstances. It is also imperative to have an adequate infrastructure in place to monitor and care for a patient in this situation. You can read more on this strategy under the Tips & Tricks title: Total Shoulder, Bad Lungs.

[/wlm_ismember]

Below is a video from our YouTube channel starting at a supraclavicular view going up to an interscalene view and repeating. Let your eyes follow the neural elements back and forth until you can recognize the pattern that occurs between these two areas. After that, focus on the other pattern changes and cues like the appearance of the scalene muscles and the movement of the subclavian artery. Starting from the supraclavicular position and sliding up to the interscalene position is a common technique used to clearly identify the nerve roots for this block.

[/nonmember]

See Also: Total Shoulder, Bad Lungs, Questions about UE Blocks Answered, Phrenic Nerve Dysfunction after ISB, Block Evaluation